Dear Reader,

The following article is the written version of the teaching I gave at Women of Valor this weekend. Below that, you will find the audio recording of my message along with the handouts I gave the women, and some additional helpful pdfs you are welcome to print or download.

Holy Conversation

“Be ye holy in all manner of conversation.” (1 Peter 1:15)

The Mussar masters teach that humility (anavah) is the foundation of all the middot — the ethical traits that shape godly character. Without humility, the other traits lose their balance: patience can turn into avoidance, generosity into control, truthfulness into cruelty.

385611147 | © Tanakrit Khangrang

Humility is more than thinking less of ourselves; it’s knowing our proper space before God and others. It allows us to speak truth without arrogance, and to listen without defensiveness. This is why humility is the key to reconciliation — especially in moments of disagreement or misunderstanding.

Conflict has a way of tempting us out of humility. We want to win the point, protect ourselves, or correct the other person. But humility changes the question we ask. Instead of “How can I make them understand me?” humility asks, “How can I better understand them?” This shift is impossible without empathy — the ability to truly see and feel what another person is experiencing.

Empathy is central to humility because it keeps our hearts soft. It guards us from assuming motives, making quick judgments, or treating others as less than ourselves. When humility and empathy work together, even hard conversations can become opportunities for connection and growth.

“People with good sense are slow to anger, and it is their glory to overlook an offense.” (Pro 19:11, CJB)

That’s why in this teaching, we will explore Nonviolent Communication (NVC),[1] a conflict resolution framework developed by Dr. Marshall Rosenberg, for practicing humility in our day-to-day conversations. NVC slows us down and helps us speak in a way that honors both our own needs and the needs of others — without judgment or accusation.

NVC works through four interconnected components:

- Observation – Describing what happened without judgment or interpretation.

- Feeling – Naming the emotion we’re experiencing in response to the observation.

- Need – Identifying the universal human value or longing connected to that feeling.

- Request – Asking for a specific action that could help meet that need.

When we approach conversations — especially conflict — with these four steps, we practice humility by refusing to assume we know it all, and we practice empathy by truly considering the other person’s reality. Together, they turn ordinary moments of tension into holy conversations.

“But the things that proceed out of the mouth come forth from the heart, and those things make the man unholy. For out of the heart come evil thoughts, murder, adultery, sexual immorality, theft, false witness, and slander. These are the things that make the man unholy; but to eat with unwashed hands does not make the man unholy.” (Mat 15:18-20, TLV)

Component 1: Observation – Seeing Without Judgment

“Set a guard, Adonai, over my mouth. Keep watch over the door of my lips.” (Psa 141:3, TLV)

Humility in conversation begins with the courage to see what’s happening without assigning blame, moral verdicts, or hidden motives. This first component of Nonviolent Communication (NVC) is deceptively simple: describe what you actually see or hear without judgment, evaluation, or interpretation.

An observation is a simple, verifiable description — what could be captured on camera or heard in an audio recording. A judgment or evaluation adds interpretation, assumption, and often a moral verdict.

“Do not judge according to appearance, but judge with righteous judgment.” (Jhn 7:24, NAS95)

Not all judgments are the same. While Adonai charges us to practice righteous judgment, most of the judgments people make about others are unrighteous. NVC makes an important distinction:

- Value Judgments express the qualities we believe serve life—honesty, freedom, kindness, peace. These reflect our beliefs for how life can best flourish.

- Moralistic Judgments are about labeling people as right or wrong, good or bad, based on whether they meet our values. They often imply that someone is “less than” or deserving of punishment if they fall short. Example: “He is lazy.” “She is selfish.”

Value judgments can lead to honest conversation about needs. Moralistic judgments usually lead to blame, insults, comparisons, and criticism — all of which close the door to empathy.

“A fool takes no pleasure in understanding, but only in expressing his opinion.” (Pro 18:2, ESV)

The Jackal Voice – Our Inner Interpreter

Moralistic judgments or evaluations can feel righteous, protective, even discerning, but it’s often fear, pride, or pain in disguise. Something triggers us—anger, anxiety, a sense of betrayal—and instead of naming our feelings or seeking understanding, we start constructing a story.

This is where unholy conversation begins:

- We label, classify, and interpret the other person’s behavior.

- We fill in the blanks about their motives and intentions.

- We replace observation with assumption or unvoiced expectations.

In NVC, the jackal symbolizes life-alienating communication. As an animal, the jackal is low to the ground, a scavenger, competitive, and fierce. As a metaphor, it represents the reactive voice inside us that views the world through right/wrong, good/bad dualities and seeks to control through fear, guilt, and shame.

“Therefore you have no excuse, O man, every one of you who judges. For in passing judgment on another you condemn yourself, because you, the judge, practice the very same things.” (Rom 2:1, ESV)

The Bible presents a morality rooted in love, not merely rules. True compassion flows from deep connection and empathy, not from obligation or fear of breaking the Law. Yeshua acted out of heartfelt compassion—sharing in people’s pain—not because He “should.” Rules can restrain behavior, but love transforms it.

Dr. Henry Cloud, in Changes That Heal, illustrates this difference with a simple analogy. Imagine I hand you a baseball bat and give you permission to hit me. One

person says, “I wouldn’t because it’s wrong.” Another says, “I wouldn’t because I don’t want to hurt you.” Which would you trust more? The one motivated by empathy. When we care how our actions affect someone we’re connected to, love—not fear of punishment—guides us toward life-giving choices.

By contrast, the jackal mindset—comparable to the lower nature or ego—is far more self-focused. When offended or in conflict, it often shows up as an “inner interpreter” that jumps to conclusions, usually without evidence. It may sound like:

- A defense attorney– “I have every right to feel this way.”

- A mind reader– “She said that because she thinks I’m incompetent.”

- A spiritual judge– “The Spirit showed me their true heart.”

- A historian– “They always do this; they never change.”

- A director– “I know where this is going; I’ve seen it before.”

“Now flee from youthful lusts and pursue righteousness, faith, love and peace, with those who call on the Lord from a pure heart. But refuse foolish and ignorant speculations, knowing that they produce quarrels.” (2Ti 2:22-23, NAS95)

“Do not be quickly provoked in your spirit, for anger settles in the bosom of fools.” (Ecc 7:9, TLV)

This voice is not neutral. It draws from our fears, wounds, and ego. The most dangerous false narratives are not those in today’s media, but the stories we create in our minds about the heart and motives of others. We tell ourselves what their words really meant, how they must feel about us, and who they must be, deep down. This sort of judgment belongs to God alone.

“Do not speak against one another, brethren. He who speaks against a brother or judges his brother, speaks against the law and judges the law; but if you judge the law, you are not a doer of the law but a judge of it. There is only one Lawgiver and Judge, the One who is able to save and to destroy; but who are you who judge your neighbor?” (Jas 4:11-12, NAS95)

The Four D’s – How the Jackal Speaks

The jackal’s inner interpreter tends to communicate in four main ways—what NVC calls the Four D’s of Disconnection:

- Deserving – Sorting people into those who deserve reward and those who deserve punishment. “She doesn’t deserve my trust after what she did.”

- Diagnosing – Judging, labeling, and making assumptions about motives.

“The problem with you is that you’re selfish.” - Denying Choice – Using guilt and blame to avoid responsibility.

“I have to do it because you won’t.” or “You made me so angry.” - Demanding – Pushing compliance through fear or control.

“You’d better do this if you know what’s good for you.”

In each case, the jackal focuses on accusing or controlling the other person instead of seeking to understand or connect.

“A single witness shall not rise up against a man on account of any iniquity or any sin which he has committed; on the evidence of two or three witnesses a matter shall be confirmed. If a malicious witness rises up against a man to accuse him of wrongdoing, then both the men who have the dispute shall stand before the LORD, before the priests and the judges who will be in office in those days. The judges shall investigate thoroughly, and if the witness is a false witness and he has accused his brother falsely, then you shall do to him just as he had intended to do to his brother. Thus you shall purge the evil from among you.” (Deu 19:15-19, NAS95)

The Four R’s – How the Giraffe Speaks

By contrast, the giraffe represents life-serving communication. With the largest heart of any land animal and the longest neck for perspective, the giraffe reminds us to speak from the heart and keep the bigger picture in view.

The Four R’s of the giraffe guide us toward humility and empathy:

- Remembering – We are all unique, interconnected, and interdependent.

- Respecting – Ourselves and others, knowing we’re all trying to meet legitimate needs.

- Taking Responsibility – For our beliefs, feelings, thoughts, and actions.

- Requesting – Inviting, not demanding, and accepting “yes” or “no” as a step toward dialogue.

Righteous judgment begins with clarity, and clarity begins with what we have actually observed. The clearest way to silence the jackal and speak giraffe is to start with an observation. An observation is a simple, verifiable description. Ask: Could this be recorded on video or audio exactly as I’m describing it? If not, it’s probably a judgment.

- Judgment/Evaluation: “You’ve been ignoring me.”

- Observation: “We haven’t spoken in two months.”

The first closes the door to dialogue; the second leaves room for the other person’s perspective. Making observations without judgment slows us down. It creates a pause in which God can work in us and in the relationship. It honors truth, preserves dignity, and keeps conflict as an opportunity for reconciliation rather than a catalyst for division.

“So take care how you listen; for whoever has, to him more shall be given; and whoever does not have, even what he thinks he has shall be taken away from him.” (Luk 8:18, NAS95)

Humility keeps us from usurping God’s role as the Judge of hearts. Observation keeps us tethered to truth instead of imagination. And empathy—rooted in humility—keeps our hearts open long enough for reconciliation to be possible.

“Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful. Do not judge, and you will not be judged; and do not condemn, and you will not be condemned; pardon, and you will be pardoned. Give, and it will be given to you. They will pour into your lap a good measure—pressed down, shaken together, and running over. For by your standard of measure it will be measured to you in return.” (Luk 6:36-38, NAS95)

When we replace the Four D’s with the Four R’s, we move from reactive, fear-based communication to relational, heart-centered conversation. This is the ground where the rest of NVC—and the work of the Spirit—can take root.

“Put away from you a deceitful mouth and put devious speech far from you. Let your eyes look directly ahead and let your gaze be fixed straight in front of you.” (Pro 4:24-25, NAS95)

Component 2: Naming Our Feelings

Taking responsibility for our own feelings is central to holy conversation. “No matter what has happened, we are all responsible for how we feel one hundred percent of the time. How we feel is a direct reflection of our thoughts, [beliefs, and values]. Change your perspective about an incident and you will change how you feel.”[2]

This shifts the focus from, “You made me feel…” to, “When this happened, I felt…” That small change keeps us from assigning blame for our emotional state and instead allows us to own our internal experience. In relationships, people often say things like, “You’re annoying me,” “That really hurt my feelings,” or “You’re driving me crazy.” This is blame language—it attributes our feelings to someone else’s behavior and makes them “wrong or bad” for making us feel unpleasant. In reality, the other person’s words or actions are the stimulus for our feelings, not the cause.

“Brothers and sisters, do not be children in your thinking; yet in evil be infants, but in your thinking be mature.” (1 Co 14:20, NASB)

Taking responsibility for emotions doesn’t mean pretending not to hurt—it means owning what is ours to steward and refusing to hand that responsibility over to someone else. It also doesn’t excuse harmful behavior in others. Instead, it ensures that our own response is governed by the Spirit rather than by emotional reactivity.

“He who restrains his words has knowledge, and he who has a cool spirit is a man of understanding.” (Pro 17:27, NAS95)

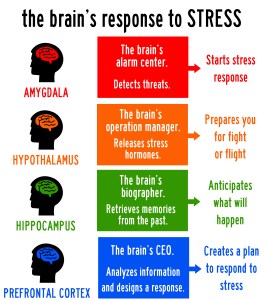

One of the most powerful tools for doing this is naming the emotion we are feeling. If we struggle to identify what we feel, it’s often because our brain is operating from the limbic system—the emotional center that includes the amygdala, our built-in alarm system. While the amygdala is helpful in emergencies, it can be destructive in relationships. Neuroscience shows that when we label our feelings, we engage the prefrontal cortex—the brain’s reasoning and empathy center. This shift helps quiet the amygdala’s alarm, regulate our nervous system, and bring clarity and calm. It’s as if naming the emotion tells the body, You’ve been heard; you can stand down now. From this grounded place, our words are more likely to be gracious and constructive.

However, naming feelings requires care. The first guideline is to differentiate between a feeling and what we are thinking. For example:

- “I feel betrayed” is an accusation, not a feeling. A nonjudgmental statement would be, “When you lied about where you were, I felt shocked and hurt, because I value honesty and faithfulness.”

- “I feel that you don’t love me enough” is an interpretation of actions (or inaction). A truer expression might be, “I feel sad and lonely when we don’t spend time together.”

- “I feel misunderstood” is an evaluation of someone else’s understanding. A more accurate statement would be, “I’m feeling anxious or annoyed about our communication.”

When we disguise thoughts and judgments as feelings, they often sound like blame. And when the other person feels blamed, their natural reaction is to defend, explain, or counterattack—shutting down connection.

“Do you see someone hasty in his words? There is more hope for a fool than him.” (Pro 29:20, TLV)

“If anyone thinks himself to be religious, and yet does not bridle his tongue but deceives his own heart, this man’s religion is worthless.” (Jas 1:26, NAS95)

Clear feelings language does the opposite. It lowers defenses because it says, “This is what’s happening in me,” rather than, “This is what’s wrong with you.” These small shifts in wording can make a huge difference in how our words are received.

Examples

- Judgment disguised as feeling: “I feel manipulated.”

Pure feeling: “I feel uneasy and anxious about this conversation.” - Judgment disguised as feeling: “I feel rejected.”

Pure feeling: “I feel lonely and hurt when I don’t hear back from you.” - Judgment disguised as feeling: “I feel attacked.”

Pure feeling: “I feel tense and unsafe when voices get raised.”

Once we’ve learned to take ownership of our own emotions, love calls us to extend the same care to others. Part of responsibility in communication is ensuring the other person’s feelings are adequately heard. Sometimes this means gently guessing what they might be feeling—not to project or assume, but to offer a bridge: “It sounds like you might be feeling… Is that right?” Even if we miss the mark, we show that their inner life matters enough for us to try.

“Let your speech always be with grace, seasoned with salt, to know how you ought to answer everyone.” (Col 4:6, TLV)

Too much or too little salt makes food inedible or unpleasant. In the same way, wise words are measured, thoughtful, and responsive—not reactive. Owning our emotions and honoring the emotions of others is one way to keep our speech seasoned with grace, opening the gates of righteous judgment in every conversation.

“Have I not wept for the one whose life is hard? Was not my soul grieved for the needy?” (Job 30:25, NAS95)

Component 3: Needs

“The wisdom of the wise is to understand his way, but the foolishness of fools is deceit.” (Pro 14:8, LITV)

If naming emotions helps us take responsibility for our inner world, identifying the needs behind those emotions helps us understand why we feel what we feel and what may lead to resolution or restoration.

Needs are the things we can’t live without like air, food, water, and shelter. But they also represent our values, wants, dreams, desires, and preferences for a happier and/or more meaningful experience as a human. Although we have different needs in differing amounts at different times, they are universal in all of us. When they are unmet, we experience feelings, and when they are met, we experience feelings.

When a need is met, we feel gratitude, peace, joy, or security. When a need is unmet, we feel sadness, fear, frustration, or discouragement. Thus, needs are not inherently sinful, but they can become dangerous when we seek to fill them apart from God or demand that others meet them on our terms. Recognizing needs gives us clarity. For example:

- Anger may signal a need for fairness, safety, or respect.

- Sadness may reveal a need for comfort, connection, or reassurance.

- Anxiety may point to a need for security, stability, or guidance.

When we stop at the surface emotion, we may misdirect our energy toward punishing someone for how we feel. But when we ask, What need is underneath this?, we invite God to show us where we are truly lacking and how He might meet us there.

“Know this, my dear brothers and sisters: let every person be quick to listen, slow to speak, and slow to anger— for human anger doesn’t produce the righteousness of God.” (Jas 1:19-20, TLV)

When we see the need beneath the emotion, our perspective shifts. Where we once assumed bad motives or sinfulness, we now see an unmet need—an opportunity for empathy instead of judgment.

“The intent of a man’s heart is deep water, but a man of insight draws it out.” (Pro 20:5, TLV)

Identifying needs is not about excusing hurtful actions, it is about moving from accusation to curiosity. It opens the possibility for understanding, for asking questions that draw out the heart, and for finding solutions that honor both parties.

In the language of holy conversation, needs become a bridge. When we can say, “I’m feeling anxious because I need reassurance about this decision,” we give the other person something concrete to respond to, something that can be discussed, negotiated, or supported. In contrast, “You’re making me anxious” blames, accuses, and closes the door.

Needs also invite prayer. When we name a need before God, we position ourselves to receive from Him first, whether through His direct comfort or through the help of others.

“Do not let any unwholesome talk come out of your mouths, but only what is helpful for building others up according to their needs, that it may benefit those who listen.” (Eph 4:29, NIV)

The Jackal and Giraffe Approaches to Needs

Jackal often disguises needs behind demands, moralistic judgments, or blame:

- “You should listen to me.” (need for being heard)

- “You’re selfish.” (need for cooperation)

- “You never spend time with me.” (need for connection)

Giraffe makes needs explicit and mutual:

- “I need to know my voice matters in our conversations.”

- “I’m longing for more cooperation as we share this workload.”

- “I’d like to spend more time together because I value our friendship.”

Four D’s of a Jackal (life-alienating needs language)

- Deserving – “I’ve worked hard all day; I deserve to be left alone.”

- Diagnosing – “You’re lazy; that’s why you didn’t help.”

- Denying Choice – “I have to do everything around here because no one else will.”

- Demanding – “You must call me every day.”

Four R’s of a Giraffe (life-giving needs language)

- Remembering – “I’m needing some rest and quiet after a long day, and I know you need time together—can we plan both?”

- Respecting – “I need help with the chores, and I respect that you’ve had a full schedule too—can we divide the tasks?”

- Taking Responsibility – “I feel overwhelmed doing this alone, and I’d like to find a way we can share the work.”

- Requesting – “I feel connected when we talk regularly—would you be willing to check in each week?”

Jackal language tells people what they’ve done wrong. Giraffe language tells people what would make life better—for both of you. When we connect our emotions to our needs, we gain insight, self-control, and compassion. We also prepare ourselves for the next step: expressing those needs in the form of a clear, respectful request, rather than a demand.

“Bear one another’s burdens, and in this way you fulfill the Torah of Messiah.” (Gal 6:2, TLV)

Component 4: Requests

“Ask, and it will be given to you; seek, and you will find; knock, and it will be opened to you. For everyone who asks receives, and he who seeks finds, and to him who knocks it will be opened. Or what man is there among you who, when his son asks for a loaf, will give him a stone? Or if he asks for a fish, he will not give him a snake, will he? If you then, being evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father who is in heaven give what is good to those who ask Him!” (Mat 7:7-11, NAS95)

If identifying observations, feelings, and needs lays the foundation, then requests are where the rubber meets the road. A request is simply an invitation to

meet a need—yours or another’s—in a way that keeps the dignity of both people intact.The request is the ebb and flow of giving and receiving, back and forth, that provides the opportunity for everyone’s needs to be met.

The difference between a request and a demand is not in the wording—it’s in the spirit behind it.

-

-

-

- A demand communicates: “Do this or else you’ll be judged, shamed, or punished.”

- A request communicates: “Here’s what I would like—are you willing?” and leaves room for freedom, dialogue, and even a “no” without retaliation.

-

-

Marshall Rosenberg observed that when people hear a demand, they immediately weigh how to protect their own autonomy. Even if they comply, it will likely be from fear, guilt, or resentment, not from a place of love and giving from the heart.

Making requests also tests the sincerity of our humility. Philippians 2:4 says, “Let each of you look not only to his own interests, but also to the interests of others.” A request honors the other person’s perspective and interests too. It says, “I value you enough to ask, not assume or coerce.”

When we turn needs into demands, we put the relationship at risk—because if the demand isn’t met, the next step is judgment and punishment, which is how idols of the heart are created. But when we turn needs into requests, we plant seeds for mutual understanding and cooperation.

Why We Avoid Requests

Many of us struggle to make clear, direct requests because we:

- Fear rejection or disappointment.

- Assume the other person “should” already know what we need.

- Confuse hinting or complaining with asking.

But unspoken expectations are a breeding ground for offense and resentment.

Making Effective Requests

In NVC, a good request is:

- Specific and Concrete – “Would you be willing to call me when you’re running late?” instead of “Don’t keep me waiting.”

- Positive – Focus on what you do want, not what you don’t.

- Present and Actionable – Something that can be done here and now, not a vague future hope.

- Mutual – Open to negotiation, recognizing the other person’s needs too.

Specific requests honor both parties’ dignity by removing guesswork and replacing accusation with clarity. A vague request, by contrast, is like leaving the gate half-shut. The other person can’t see clearly what you are asking, and the conversation is more likely to be derailed by assumptions, defensiveness, or hurt.

To ensure our requests are clear and specific, it is helpful to ask the other person one of the following questions:

- “How do you feel about what I just asked for, and why?”

- “Do you think this approach will work?”

- “Do you feel what I’m asking is reasonable?”

These follow-up questions communicate that our request is not a demand but an opening for partnership. They turn the conversation from a one-sided declaration into a two-way bridge that can bear the weight of empathy, creativity, and mutual care.

Two Parts of NVC: Speaking and Listening in Humility

- Expressing With Honesty

When we express ourselves with honesty and vulnerability, we give others the gift of knowing our heart without them having to guess. This means:

- Honestly expressing nonjudgmental observations, your own feelings, and needs.

“When I hear (or see)… I feel… because I need… Would you be willing to…?” - Having the courage to be vulnerable instead of hiding behind blame or generalizations.

- Making clear, detailed requests rather than hinting, complaining, or assuming the other person “should just know.”

Humility allows us to expose our needs without shame, trusting that the other person can respond freely—yes, no, or with a counter-proposal—without it diminishing our worth.

- Listening With Empathy

“The one who states his case first seems right, until the other comes and examines him” (Proverbs 18:17).

Providing empathy means listening in a way that draws the other person out and helps them connect with their own heart. It requires:

- Presence – staying focused on them without distraction.

- Space – resisting the urge to jump in with your own story or opinion.

- Verbal reflection of feelings and needs: “Are you feeling…?” “Are you needing…?”

- Avoiding the habits that shut down connection: Advising, Fixing, Consoling, Storytelling, Sympathizing, Analyzing, Explaining, Defending

In this mode, no matter what is said, we listen for only four things: observations, feelings, needs, and requests. We don’t rush to respond with our own request unless invited—either by a sign from the other person that they are ready or by an explicit ask.

Holy conversation is more than polite speech, it is a way of life shaped by humility, truth, and love. It guards the “gates” of our words so that what passes through builds bridges, not walls. When we practice awareness, avoid premature judgments, own our emotions, identify the needs beneath them, and make gracious requests, we participate in God’s work of reconciliation. In speaking this way, we reflect the Messiah, who is “full of grace and truth” (John 1:14). Our manner of life—our conversation in the biblical sense—becomes a living witness of the Kingdom of Heaven.

“The path of the righteous is like the light of dawn, shining brighter and brighter until the full day. The way of the wicked is like darkness. They do not know what makes them stumble.” (Pro 4:18-19, TLV)

Recap of the Four Steps

When I see (or hear)…

I feel…

because I need/value…

Would you be willing to…..

Helpful PDF Files:

BASIC NVC MODEL PDF (includes list of feelings & needs)

NVC Practice (worksheet)

WOV Retreat Recording & Slides:

Holy Conversation (pdf of slides used in the audio version at WOV)

Related Links:

Revive 2025 – Humility: Where Heaven Meets Earth (my message begins at 1.08 hr mark of session 2)

Rom 12:9-18 (NAS95) Let love be without hypocrisy. Abhor what is evil; cling to what is good.

10 Be devoted to one another in brotherly love; give preference to one another in honor;

11 not lagging behind in diligence, fervent in spirit, serving the Lord;

12 rejoicing in hope, persevering in tribulation, devoted to prayer,

13 contributing to the needs of the saints, practicing hospitality.

14 Bless those who persecute you; bless and do not curse.

15 Rejoice with those who rejoice, and weep with those who weep.

16 Be of the same mind toward one another; do not be haughty in mind, but associate with the lowly. Do not be wise in your own estimation.

17 Never pay back evil for evil to anyone. Respect what is right in the sight of all men.

18 If possible, so far as it depends on you, be at peace with all men.

[1]https://www.amazon.com/s?k=nonviolent+communication&crid=19GEAEWQX0XML&sprefix=nonviolent%2Caps%2C185&ref=nb_sb_ss_p13n-pd-dpltr-ranker_1_10

[2] Salaberrios, Micah. The Art of Nonviolent Communication: Turning Conflict into Connection (p. 22). Brackets added by K. Gallagher

Images licensed from Dreamstime.com